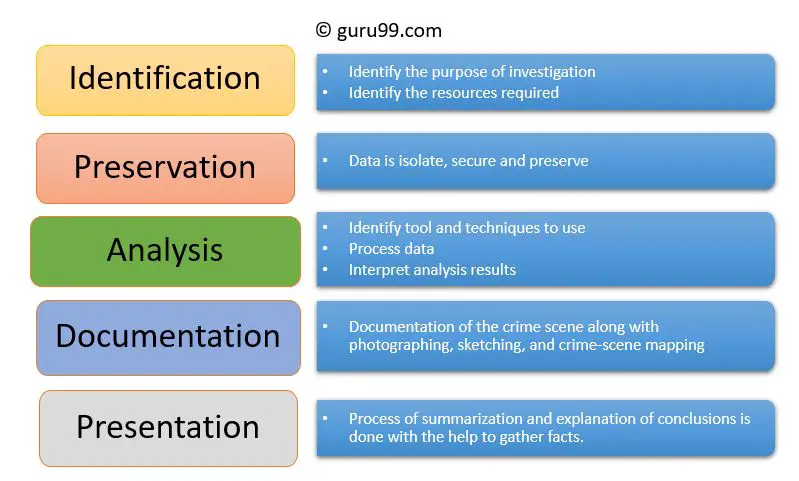

Computer forensics, also known as digital forensics, is the process of examining digital devices and digital data to gather evidence for use in legal proceedings. The typical computer forensic examination consists of four main steps: acquisition, analysis, documentation, and presentation.

The goal of a computer forensic examination is to identify, preserve, recover and analyze data while maintaining its integrity and evidentiary value. Examiners follow strict procedures and use specialized tools to ensure the data they collect can be authenticated in court.

Computer forensics is used in a variety of investigations, including hacking, fraud, espionage, murder, and more. By thoroughly analyzing digital evidence, forensic examiners can help reconstruct events to determine if a crime was committed.

Step 1: Acquisition

The first step in a computer forensic examination is acquiring the digital evidence. This involves making a forensic copy or “image” of the data. The examiner creates a bit-for-bit copy of the original evidence, preserving the data without making any changes or alterations.

Proper evidence acquisition is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the data. Examiners use write-blocking tools and hardware to prevent the original evidence from being modified during the imaging process. Write blockers work by either physically stopping write commands or logically changing write commands into read commands.

Common practices for evidence acquisition include:

- Removing hard drives from a computer and connecting them to a write-blocking device.

- Booting the computer into a boot disk or forensic operating system.

- Imaging removable media like USB drives, CDs, DVDs, etc.

- Creating a logical image of files and folders.

- Capturing network traffic and logs.

- Using forensic tools like EnCase, FTK, or Nuix for data acquisition.

The forensic copy created during acquisition is used for the remainder of the examination rather than the original evidence. This protects the integrity of the original data and maintains the chain of custody.

Why Proper Acquisition is Important

Proper acquisition techniques are important for several reasons:

- Prevents data alteration – Write blocking guarantees the original evidence is untouched.

- Supports authentication – Using forensic tools and hashes proves the copy’s authenticity.

- Maintains chain of custody – Following protocols demonstrates the evidence was handled correctly.

- Allows repeat examination – The working copy can be analyzed repeatedly without risk.

- Captures live data – Tools can often image live systems while active.

- Recovers deleted data – Skilled examiners can retrieve hidden and deleted data.

Overall, proper acquisition lays the foundation for a thorough, defensible examination that can withstand legal scrutiny.

Step 2: Analysis

The second step of a computer forensic examination is analyzing the acquired data to identify and extract evidence. Examiners use a variety of techniques and tools to uncover relevant files, artifacts, metadata and other information.

Some common analysis techniques include:

- Keyword searches – Search for specific files, emails, documents, etc. containing keywords.

- Data carving – Extracting raw data from disk and memory based on headers, footers, file structures.

- Metadata review – Examine file metadata like timestamps, ownership, edits.

- Link file analysis – Identify relationships between files based on physical location, time of creation, associated software, etc.

- Memory analysis – Review running processes, network connections, passwords in volatile memory.

- Log analysis – Parse activity from system logs, firewalls, antivirus tools, etc.

Examiners use forensic analysis tools such EnCase, FTK, Internet Evidence Finder, and many open source tools. The tools help automate searches, provide unique capabilities, and generate reports from the data.

Key evidence uncovered during analysis may include:

- Deleted files – Recovered using data carving or undelete tools.

- Internet history – Web pages, downloads, search terms.

- Emails – Mailboxes, attachments, contacts.

- Documents – Hidden, encrypted, or suspicious files.

- Images/video – Photos, graphics, media files.

- Network data – IP addresses, DNS queries, remote logins.

- File metadata – Creation/edit/access dates, authors.

- Data remnants – Temporary files, file fragments.

- Operating system artifacts – Logs, registry data, memory dumps.

- Encrypted data – Cracked passwords, encryption keys.

Thorough analysis takes time but can uncover traces of activity the user never intended to leave behind. This data allows examiners reconstruct events and provide evidence of the who, what, when, where, and how surrounding the crime.

Importance of Methodical Analysis

Careful, methodical examination and analysis is crucial for an effective investigation. Proper analysis ensures:

- All data is thoroughly reviewed – Multiple passes may uncover deleted or obscured data.

- Findings are reproducible – Detailed notes allow independent third-party review.

- Information is discovered in context – Link file analysis reveals the big picture.

- Exculpatory evidence is identified – Analysis should reveal evidence favorable to the accused when present.

- Evidence is recovered in a forensically sound manner – Using court-validated tools and techniques.

- Conclusions are formed objectively – Without bias or assumptions interfering.

Overall, methodical analysis provides the details needed to draw accurate, reliable conclusions from the digital evidence.

Step 3: Documentation

The third step in the forensic examination process is thoroughly documenting the acquisition, analysis, and findings. Documentation provides a detailed record that allows the examiner to reconstruct their entire methodology and reasoning.

Forensic documentation should include:

- Case details – Background, allegations, assignment.

- Hardware/software used – Make, model, versions, configurations.

- Data acquisition – Tools, procedures, hash values, verification, chain of custody.

- Analysis process – Tools, techniques, repeatability, quality control.

- Findings – Artifacts, relevant data, reconstruction of events.

- Visual aids – Screen captures, logs, evidence, charts.

- Opinions and conclusions – Clear explanations of implications and significance of evidence.

Detailed documentation demonstrates the examiner followed best practices and helps convince others the findings are reproducible and verifiable. Thorough notes also refresh the examiner’s memory if they must testify months or years later.

Standard formats for documentation include case notes, logs, reports, photo logs, lab requests, evidence inventory, and chain of custody forms. Some forensic tools have built-in case management and reporting features. Using standardized templates ensures consistency across examiners and cases.

Purposes of Documentation

Robust documentation serves many important purposes:

- Shows methodology was reliable and findings are reproducible.

- Demonstrates chain of custody was maintained.

- Facilitates technical review by other experts.

- Provides basis for sound forensic conclusions and opinions.

- Jogs examiner’s memory months or years later.

- Creates persuasive, convincing presentation of findings.

- Records exculpatory evidence if discovered.

- Memorializes the entire forensic process.

By thoroughly documenting their actions and observations, the examiner creates a record that can withstand tough scrutiny in legal proceedings or reviews.

Step 4: Presentation

The final phase of a computer forensic examination is presenting the findings. Examiners share the results through reports, exhibits, depositions, and courtroom testimony. Effective presentation conveys technical findings in an understandable, persuasive manner.

Typical presentation methods include:

- Report – Detailed written report explaining methodology, evidence, and conclusions.

- Exhibits – Visual aids like charts, graphs, timelines, to illustrate key points.

- Deposition – Oral testimony and cross-examination under oath, recorded by a court reporter.

- Court testimony – Live testimony explaining methods, findings, and opinions to a judge and jury.

The forensic report pulls all documentation together into an organized, cohesive package. It summarizes the major facts and evidence in plain language. Supplementary exhibits, photos, video, or audio make technical concepts more accessible. The report forms the foundation for legal proceedings and future testimony.

In depositions and on the witness stand, the examiner verbally conveys findings, draws connections between evidence, and offers expert opinions. Presenters must translate technical details into clear explanations a layperson can digest. Strong communication skills are essential.

Keys to Successful Presentation

Characteristics of an effective forensic presentation include:

- Straightforward, plain English explanations of technical details.

- Emphasis on key findings using summaries, visuals and repetition.

- Consistent methodology and terminology across all outputs.

- Logical flow from background through evidence to final conclusions.

- No assumptions or personal opinions asserted as fact.

- Professional demeanor and appearance.

- Short, concise answers during cross-examination.

An organized, clearly communicated presentation convinces readers or jurors the examiner followed best practices and reached sound conclusions based on the digital evidence.

Conclusion

In summary, a computer forensic examination contains four key phases:

- Acquisition – Imaging hard drives, media, network data, etc. while preventing alteration.

- Analysis – Methodically reviewing data, uncovering hidden artifacts and evidence.

- Documentation – Detailing methodology, findings and reasoning in notes, reports, logs.

- Presentation – Conveying complex technical findings in plain language to investigators, lawyers, judges and juries.

By following best practices at each phase, forensic examiners can deliver court-defensible evidence to successfully resolve high-stakes investigations and cases. Proper acquisition ensures evidence integrity. Careful analysis finds relevant data. Detailed documentation memorializes the process. Effective presentation communicates findings in an accessible manner. While the exact steps vary by case, following this structured approach results in forensically sound, impactful examinations.